Hope & Remembrance

A Changemaker Interview with Cheryl Rattner Price and Debra Feldstein of The Butterfly Project

When I was fifteen, I experienced one of the most profound learning experiences of my life in my sophomore English class when we were assigned the dreaded “I-Search paper.” Unlike many research papers, the focus of the project was not merely the subject, but chronicling the research process itself.

It was a quarter-long endeavor that required hundreds of note cards, over twenty primary sources, and a live interview, all focused on a historical person of our choice. I chose Anne Frank.

In the late 80s, the Holocaust was not commonly taught in classrooms. Having read her diary, I was curious to know more. The project proved to be challenging both academically and emotionally. At first, I was shocked to discover how difficult it was to find information beyond the diary about Anne and her family. I had librarians helping me find microfiches of old newspaper articles and translate documents into English. As I called Jewish organizations seeking leads, I also learned about the Jewish community and how important learning about the Holocaust was. They were invested in my little research project to the point that I even received a return call from the head of education at the Simon Wiesenthal Center from a payphone at night.

Fueled by a sense of purpose, I was deeply committed. The culmination of learning, though, came when one of the Jewish organizations connected me with a Holocaust survivor named Hannah. Like Anne Frank, Hannah had been in hiding in Holland during the war. I visited her in her home to conduct my “interview,” and my perspective on human suffering was forever changed. I cannot accurately put into words the impact that interview had on me.

Fast forward to 2014. Now the English teacher, I was asked to create and teach a class in Holocaust Literature. Reflecting on my own learning experience as a high schooler, I understood the significance and responsibility that came with this assignment. But where to begin? Of course, much has changed in the way of research since the 1980s, but I knew if I wanted to do this course justice, I would need to take my students to that deeper, more personal level.

I delved into a plethora of online sources and connected with Jewish organizations specializing in Holocaust Education (see resources below). I sought training and ways to bring the stories of the Holocaust thoughtfully into my classroom. I was particularly looking for a way for my students to emotionally process the poems written by the children incarcerated in Terezin. This is how I came across a beautiful organization called The Butterfly Project and first met Cheryl Rattner Price. It was a moment of Bashert (the Yiddish word for destiny).

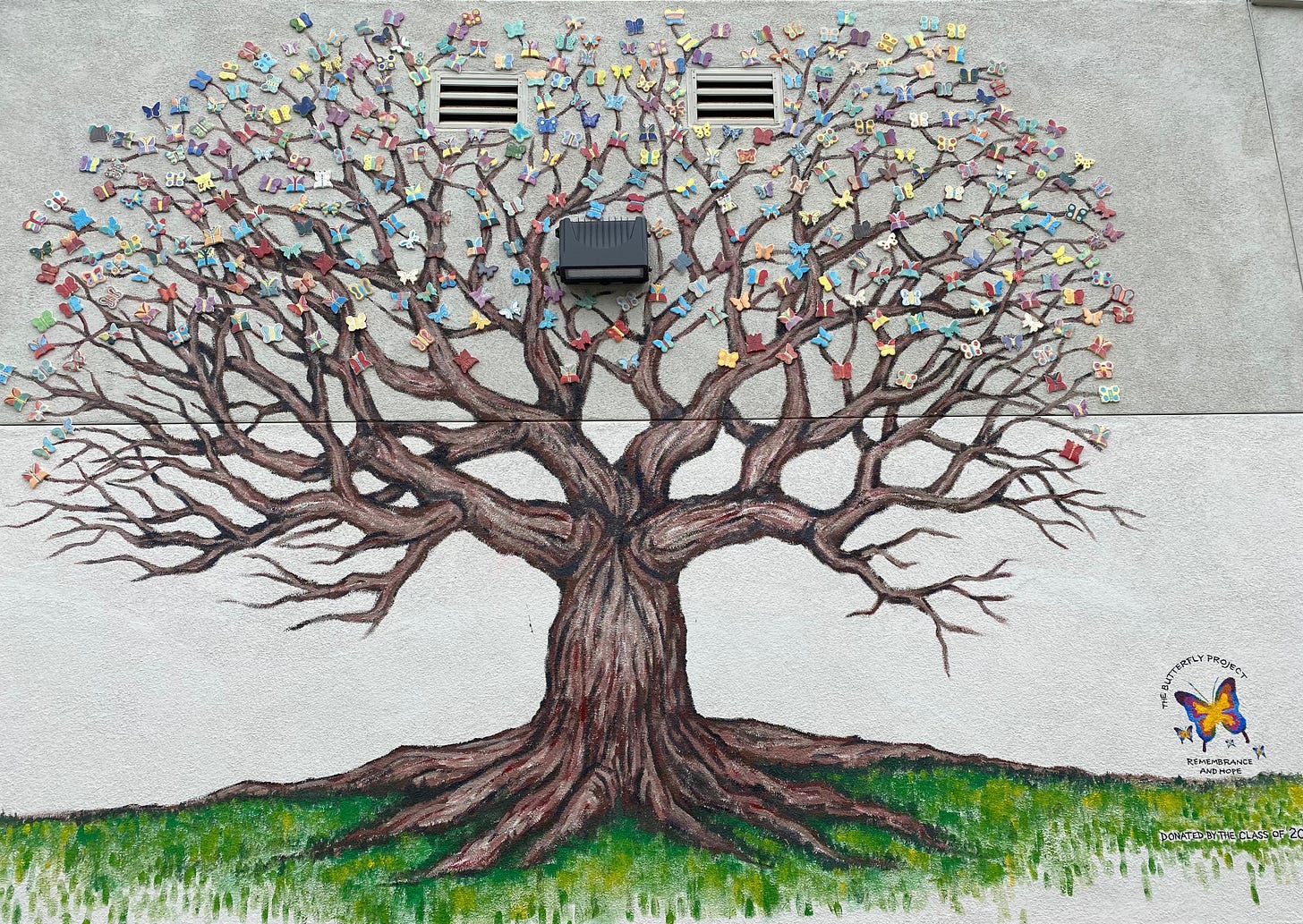

“The Butterfly Project (TBP) was co-founded by San Diego Jewish Academy educator Jan Landau and artist Cheryl Rattner Price as a new approach to teaching the Holocaust that is hands-on, hopeful and profound, collectively memorializing the 1.5 million children murdered during the Holocaust, and honoring the survivors.” (The Butterfly Project Website)

Today, The Butterfly Project approach has been adopted by over 200 communities worldwide. In this year of the 80th Anniversary of the Liberation of Auschwitz, I felt compelled to revisit the importance of remembering and learning from the past. So, for this month’s Changemakers interview, I chatted with Co-founder Cheryl Rattner Price and Debra Feldstein, the Executive Director of The Butterfly Project, to gain a deeper understanding of the work they do. Here is that interview, slightly edited for length and clarity.

Tell me a little about your background and how it led you to the work you’re doing now.

CHERYL: My background as an artist began in elementary school and it offered me an area of comfort as a shy and insecure kid. Landing on art allowed me to get lost in my imagination and was a safe place for me. I became passionate about ceramics, working in an isolated way, mainly on commissions. When my kids started at the San Diego Jewish Academy (SDJA), I was conflicted about how to focus on my kids and on my work.

When SDJA asked me to be their artist in residence, it completely transformed my life. I became involved in creating community art that was spiritually informed. I worked with people of all ages and devoted myself to sparking confidence in others to feel safe enough to explore their creativity. I was tasked with creating a big sculptural ceramic mosaic piece on campus, with the students’ families, teachers, and rabbis, bringing people together around a common cause.

A few years later, SDJA educator and Director of Special Programs, Jan Landau, my co-founder, asked me to join her and bring my art to this Holocaust remembrance project. I wasn’t sure I wanted to do it, but I felt obliged. I had a bit of a scary experience as a child with a Holocaust survivor who taught me piano. I look back with regret that I quit. She had been through a lot of trauma, and I didn’t know how to handle it. So, when Jan introduced this idea about working with survivors, I was nervous.

There was no need to be nervous; their warmth and enthusiasm directed towards us galvanized our energy in growing The Butterfly Project. I was fascinated by many of these survivors, true living legends who somehow found a way to rebuild their lives and find love and purpose out of their pain and grief. I really wanted to do something meaningful that would honor them and show how we would remember their stories by creating something beautiful together.

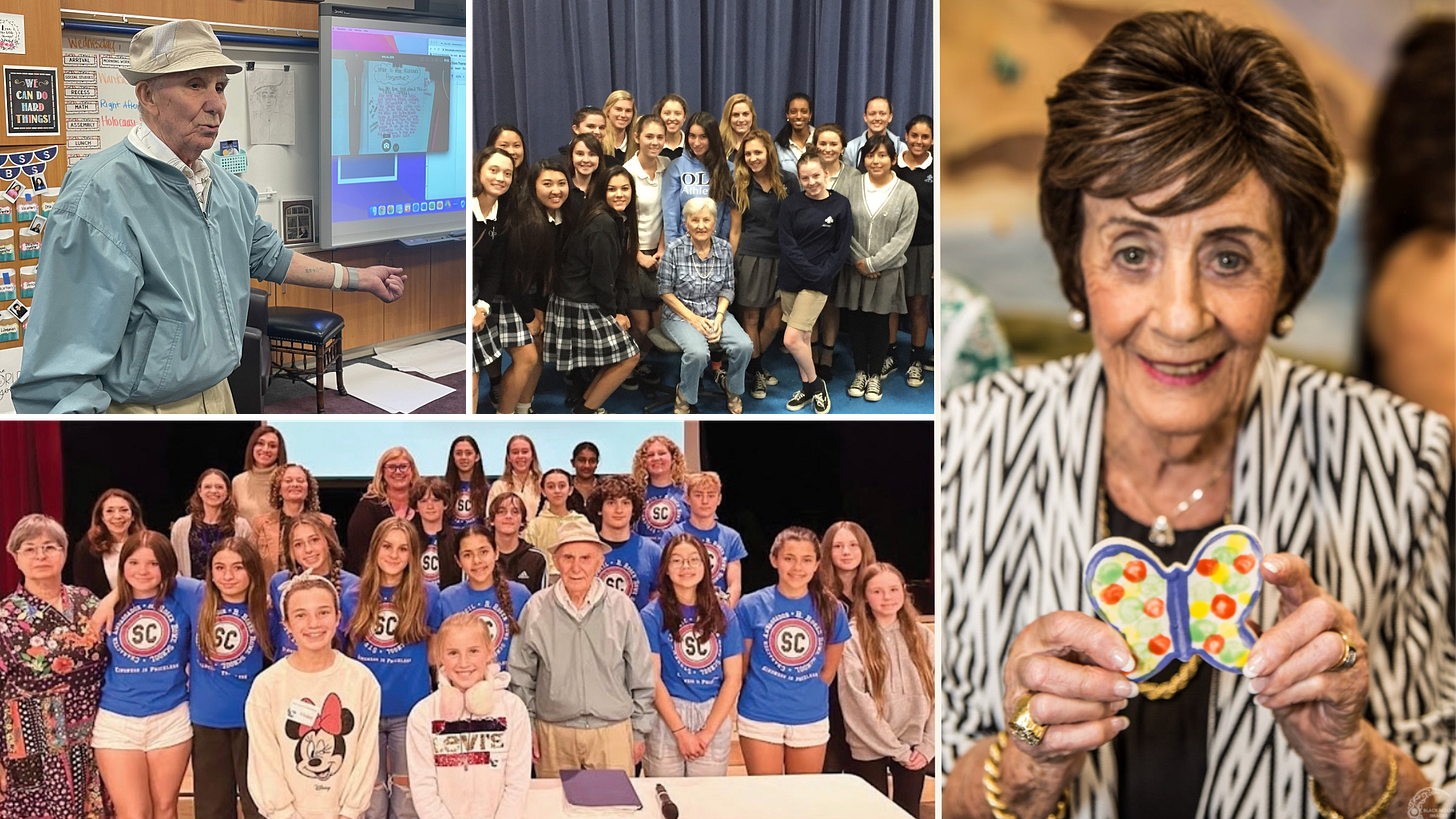

So little by little, I became braver, taking on bigger projects and installations, expanding to other schools, museums, and community centers around the country. We made the documentary film, NOT The Last Butterfly, and traveled to some amazing places sharing the project. But all in all, the magic is in the people of all backgrounds – the students, the teachers, the survivors and their families, centered around the beautiful memorial making. It’s the reminder that we need to find a way to keep hoping even in the darkest times.

“...the magic is in the people of all backgrounds – the students, the teachers, the survivors, their families, it’s the beauty. It’s the reminder that we need to find a way to keep hoping even in the darkest times.” ~ Cheryl Rattner Price

DEBRA: I grew up, different from Cheryl, in a strong and vibrant Jewish community outside Chicago. Judaism was something I was able to take for granted growing up. My teachers were Jewish, our schools were closed on the holidays, and we weren’t overwhelmed by Christmas everywhere if we didn’t leave our little community. I went to camp, which wasn’t officially Jewish, but everybody there was Jewish. Then I went to Tufts University, which at the time probably had around a 30% Jewish population. So it was just woven into the fabric of my life. I was surrounded by the culture, the community, the food, and never really suffered discrimination. I heard about discrimination, but it didn’t really sink in until I started experiencing things differently through the eyes of my children.

So I went to college, studied abroad in Israel, went to law school, and went to business school. I was at Brandeis, focused on the public sector and non-profit management. I was working for City Year, an Americorps Program, and received a call from a rabbi at Tufts Hillel, looking for a Development Director. I accepted the job because I didn’t have a job, and I didn’t want to be a lawyer anymore. And because I’m active in the community, extroverted, and see asking for money as a privilege to help people invest in something they care deeply about.

At the time, there was a shift in the Hillel movement’s leadership, from traditional rabbinical leadership to recognizing that organizations on campus needed a different set of skills. This is getting to how Cheryl and I were able to transfer from a more visionary leadership to something more strategic and practical. So I was recruited to be the Hillel Director at Stanford University. I was the first female, non-rabbi in this role and faced a lot of challenges. But I was successful, and I realized that building and growing organizations is what excites me.

So when Cheryl and I met, the story was familiar. I was excited by Cheryl and how inspiring she is, her vision, her passion, and her commitment. I also saw some real potential for growth.

Tell me why you’re passionate about this work.

DEBRA: When it comes to The Butterfly Project, there’s just something so unique, impactful, and beautiful about this model. Yes, there are a lot of Holocaust education programs, and yes, every one is important, but The Butterfly Project is this beautiful complement to any and all other curriculum. What we do is unique. First, it meets the diverse learning needs of students. They know that they are painting something meaningful. They read the card about the child that butterfly represents. It’s tactile. It’s differently meaningful.

Second, it’s the installations and permanent memorial. But we are planting seeds. And those seeds grow. They’re reminded of what it represents.

Why do you believe the work of The Butterfly Project is essential to improving our society?

CHERYL: Well, I’ll start with attention span. Young people today are checked out often, they’re outwardly focused (i.e., social media), they’re perhaps not reading, etc. So there’s something that happens with The Butterfly Project because it’s not a lecture. It’s a hands-on experience. There’s an emotional component. There’s a vulnerability. There’s the shock and fear of this actual history. It’s a wake-up call.

With TBP, a young person has the ability to take action along with other people, as a community, so it’s not all on their shoulders alone. They don’t feel as overwhelmed, and it’s character-strengthening. They can hear and process a very difficult history, and feel like they are contributing and making a tribute of some sort – some small bit of light and hope. I think this changes them in the future when they next hear something about the Holocaust. They remain curious to learn more, as opposed to how I shut down from the harsh way I was taught this topic as a child. We aim to create a softer way into this difficult topic, which allows students to be open to learning more about it. And find their empathy and ability to choose kindness.

“They can hear and process a very difficult history, and feel like they are contributing and making a tribute of some sort – some small bit of light and hope.” ~ Cheryl Rattner Price

DEBRA: Well, two reasons actually. I was recently challenged by someone about why we continue to promote Holocaust education. Because we still have lots of antisemitism. And whether or not there’s a link between awareness, knowledge, and people’s beliefs and feelings about Jewish people.

One analogy I used was that we still have a lot of racism, but we haven’t eliminated slavery from our history books. And when we think about what defines us (the Jewish community) as a people, we go back to the Holocaust. It is truly a ‘Never Forget’ moment. The survivors themselves will only survive for so long. It is our obligation to tell their stories, and the stories of the children who never got to live their lives. We have second generations who are an essential component of our project.

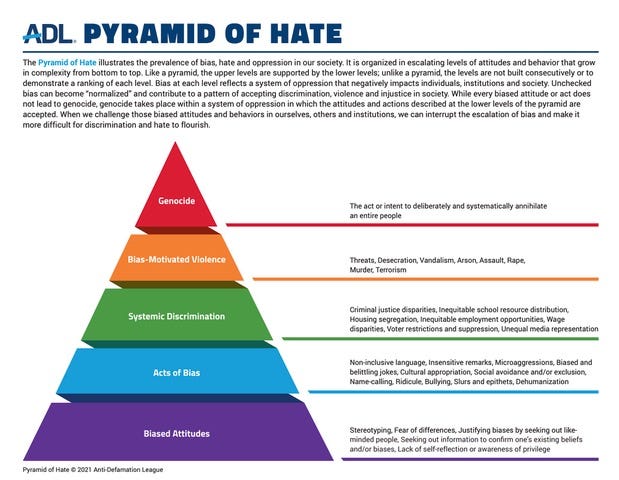

This work has to be institutionalized. The lessons of the Holocaust are broader. We see that other genocides are happening, and the world is not speaking up. So the broader lessons apply everywhere. If we look at The Pyramid of Hate, we have young people recognize that words matter, symbols matter, kindness matters, and inclusion matters.

How have you seen programming like The Butterfly Project make a positive impact?

CHERYL: I always remember the impact we had on a sixth-grade student in the Santee School District when one of our presentation teams was out there. They had some problems. One of the teachers was Jewish, and one of the kids was obnoxious enough to point out she had a Jewish nose, and there were some swastikas scratched into a desktop. They called The Butterfly Project to do what we do. At the midway point in one of the lessons, one of our teachers showed the group her father’s uniform (from the concentration camp), and she noticed this boy in the back of the class was crying.

Being sensitive, she didn’t do anything at the moment, but asked the kid afterwards, “What’s going on? Are you ok?” And he said, “I did not think this was real. I did not think this was real.” So basically, there was a full circle, where he was able to open up about what he had done and that he had not understood. I know that affected everyone in that class, for sure. There are so many more. Seeing the pride of ownership on young people’s faces when they have an installation that they’re proud of. I think about The Academy of Our Lady of Peace (side note: this was the school where I taught), and seeing the ownership that young people take over what they have learned. It has an impact. They take that with them and are proud of creating something that is a legacy.

What are some of the biggest challenges you have faced in running programming like this? How did you overcome those challenges?

CHERYL: From the artistic side, logistically with the ceramics, teachers may not have access to a kiln or may have concerns about getting their school to agree. I took it as a personal challenge to support teachers in finding a way to fire their butterflies because I wanted them to see the fulfillment and not just have the butterflies sitting on a shelf. Sometimes it takes time, but most teachers continue year after year and eventually make a display. Another challenge is the reality that teachers are strapped for time. Sometimes they need support to understand how they can integrate the program into their curriculum. And sometimes there’s a challenge because of the small cost involved.

DEBRA: There are hundreds of organizations, and if we had the bandwidth to connect with them all, we could transform this movement. The cost per child for participation is low. We just placed our largest order for butterflies ever, ordering 100,000 from our distributor in Mexico. However, we rely heavily on volunteers and need funding to support our staff and conduct outreach. It’s about bandwidth.

How has the work that you do through The Butterfly Project evolved over the years?

DEBRA: So this little program that was started by these two moms/teachers in a classroom in San Diego has blossomed into an international program. At the same time, we have a modern challenge around antisemitism, threats to Holocaust education, and we can’t afford for this not to succeed and not to grow. Are we able to move the needle? Are we able to make a transformational impact? Can we broaden this message?

So, how we think about strategic growth for our organization and ensure a sustainable, high-quality experience, we have to go from a grassroots organization to a national and international movement. That is the umbrella under which we are currently operating. It is in process to achieve that.

Is there anything special you are doing as an organization to honor the 80th Anniversary of the end of the Holocaust?

DEBRA: It’s a reminder that no one who survived is less than 80 years old. Personally, I think these anniversaries are important, but I don’t think they should increase or decrease our emphasis on the importance of the work. We’re also mindful of not exploiting the experiences of others for the benefit of our organization, even though our mission is to continue their message. So we want to be thoughtful and gentle about how we acknowledge the moment.

A significant portion of Holocaust education has centered on survivors sharing their personal stories. How are you adapting your approach to keep education going as survivors pass on?

CHERYL: I’m so glad you asked that. Our education team has four retired educators who are also second-generation. So that team has already more than doubled. We even have some third generation. This is a whole new level of expansion that we don’t have the bandwidth for everywhere, but we’re piloting it.

There’s training that goes on for the second generation to be able to tell their stories and integrate with The Butterfly Project meaningfully. There are testimonies available that students can be challenged to make and weave presentations from, but mainly it’s from things like the power of Zoom, where we have done some giant presentations in auditoriums in states where they don’t have any Jewish people or any survivors.

It’s storytelling.

I want to thank both Cheryl and Debra for taking the time to talk with me. I never imagined that a research paper in the 10th Grade would lead me to eventually teach an entire literature course about the Holocaust. And just as that research paper on Anne Frank changed me, connecting with Cheryl and The Butterfly Project in my role as an educator was transformative. They are teaching compassion, remembrance, and hope – one butterfly at a time.

Thank you for spending time reading my words and thoughts. I wish you a wonderful week! 💗

ⓒ Angie Gascho 2025. All rights reserved.

Resources - If you want to learn more!

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM)

TOLI (The Olga Lengyel Institute for Holocaust Studies and Human Rights)

The Holocaust: Remembrance, Respect, and Resilience (This is a free online textbook I helped peer edit.)

Just trying to get back to my reading. What an amazing interview Angie thank you for doing this.

Yours is the second post about this subject I've read in the last two days. The other is here: https://open.substack.com/pub/thewilderthings/p/from-a-metaphysical-point-of-view?r=1eqm6v&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=false

Both worth reading.